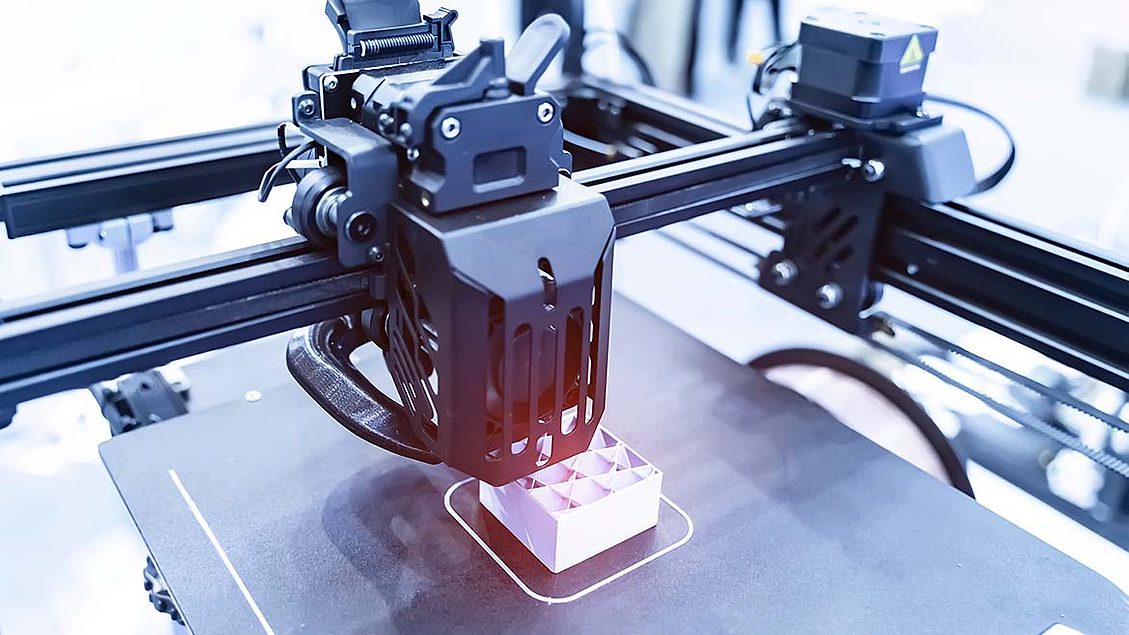

Additive manufacturing (AM), often referred to as 3D printing, has changed how metallic components are designed and produced, enabling layer-by-layer fabrication directly from digital models. AM allows the creation of geometrically complex and lightweight structures that were previously impossible to manufacture using conventional methods. These capabilities create new quality assurance challenges, particularly for verifying internal consistency.

Nondestructive testing (NDT) plays a crucial role in ensuring that AM components meet stringent mechanical and structural integrity requirements, especially for aerospace, nuclear, and defense applications. Among the various NDT modalities available, neutron imaging has emerged as a powerful and complementary method to traditional x-ray and computed tomography (CT) inspection.

Neutron radiography and neutron computed tomography (nCT) provide unique capabilities for examining internal features of metallic AM parts, particularly in cases where x-rays struggle to reveal critical defects or material inconsistencies. This article examines the fundamentals of neutron imaging, its advantages over x-rays for dense metallic structures, and its growing importance in verifying the consistency and reliability of additively manufactured components.

Fundamentals of Neutron Imaging

Neutron imaging is a transmission-based nondestructive testing technique similar in principle to x-ray radiography. In both methods, a beam of penetrating radiation is directed through a component, and the transmitted intensity is recorded to produce a two-dimensional projection or a three-dimensional reconstruction. However, while x-rays interact primarily with the electron clouds of atoms, neutrons interact with atomic nuclei. This difference creates contrast mechanism based on nuclear scattering and absorption cross-sections rather than electron density.

Neutron Sources and Detection

Neutrons for imaging are typically produced from:

- Nuclear reactors, which provide high-flux continuous neutron beams.

- Spallation sources, which generate pulsed beams by bombarding heavy metal targets with high-energy protons.

- Linear Accelerator-based systems, for industrial applications, which produce neutrons via (p,n) or (d,n) reactions.

Once transmitted through the sample, neutrons are detected indirectly. Because neutrons carry no charge and cannot ionize detectors directly, they are converted into detectable photons using neutron-sensitive converter layers or scintillator screens. These photons are then imaged by high-resolution cameras or digital detectors, forming radiographs or tomographic datasets.

Interaction Mechanisms

Neutron attenuation is governed by the material’s microscopic cross-sections for absorption and scattering, which do not follow a simple atomic-number relationship like x-rays. Light elements such as hydrogen, lithium, and boron, which are nearly transparent to x-rays, can strongly attenuate neutrons. Conversely, many heavy metals such as nickel, titanium, and tungsten, which are opaque to x-rays, may allow significant neutron transmission.

This non-linear and element-specific interaction behavior makes neutrons particularly valuable for imaging metallic systems with light-element inclusions, internal cooling channels with trapped hydrogen-bearing residues, or multi-material assemblies where x-rays provide limited differentiation.

Neutron Imaging of Additively Manufactured Components

Additive manufacturing processes such as laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) and directed energy deposition (DED) build parts through localized melting and solidification. While these methods enable precise material placement, they also introduce several potential sources of variability and defect formation:

- Porosity and lack of fusion due to insufficient energy density.

- Microcracks and shrinkage voids from rapid thermal gradients.

- Powder contamination or un-melted particles embedded in the matrix.

- Internal stress and distortions arising from complex heat cycles.

Conventional x-ray radiography or CT can effectively detect some of these defect types, particularly in small or thin components. However, as AM parts become thicker, more complex, or composed of high-density metals like Inconel or tungsten, x-rays often face limitations in penetration and contrast. This is where neutron imaging demonstrates significant advantages.

Advantages of Neutron Imaging Over X-Ray

1. Superior Penetration in Dense Metals

Because neutron attenuation does not increase linearly with atomic number, neutrons can penetrate materials that are virtually opaque to x-rays. For example, in a dense nickel-based superalloy, x-rays may be completely absorbed after only a few centimeters of thickness, while thermal neutrons can traverse many centimeters of material with measurable transmission.

This penetration capability allows inspection of thicker AM sections—such as turbine blades, heat exchangers, or combustion chambers without destructive sectioning or prohibitively high x-ray energies.

2. Enhanced Sensitivity to Light Elements

Neutrons are especially sensitive to light elements such as hydrogen, lithium, carbon, and boron—elements that play key roles in AM processes and post-processing treatments. Residual hydrogen from powder moisture, trapped lubricants, or cleaning solvents can cause embrittlement and corrosion. Neutron radiography can visualize hydrogen-containing phases, water ingress in internal cooling channels, or even polymeric infiltration in metal-polymer hybrid structures.

This sensitivity proves is particularly valuable for assessing cooling channels, additive lattices, or composite AM components where fluid pathways or light-element inclusions require verification.

3. Multi-Material Contrast

Unlike x-rays, where attenuation increases monotonically with atomic number, neutron attenuation varies irregularly across the periodic table. As a result, neutron imaging can distinguish between elements that have similar x-ray attenuation characteristics.

For example, titanium and aluminum may appear with similar contrast in x-ray images but show markedly different contrasts in neutron images. This capability enables elemental or phase differentiation in multi-material AM structures, dissimilar metal joints, or embedded sensors.

4. Complementarity to X-Ray and CT

In practice, neutron imaging is not a replacement for x-ray inspection but a complementary tool. By combining both modalities, engineers can obtain a comprehensive view of both the heavy and light-element distributions within an AM part.

For example, a dual-modality inspection might use x-ray CT to characterize metallic porosity and dimensional accuracy, while neutron CT identifies water ingress, trapped binders, or hydrogen-related defects. This synergistic approach enhances overall defect detectability and reliability verification.

Applications for Additively Manufactured Parts

Porosity and Internal Defect Detection

Porosity remains one of AM’s most persistent challenges. Neutron radiography detects void clusters or lack-of-fusion defects even in thick-walled sections where x-ray penetrate fails. Neutron computed tomography n(CT) maps these defects in three dimensions, enabling correlation with specific process parameters or build orientations.

Residual Powder and Binder Detection

In binder jetting or metal-polymer composite printing, residual binder or trapped powder significantly impacts performance. Neutrons can reveal the presence of organic residues or un-sintered powders due to their hydrogen and carbon content, aiding process qualification and cleaning validation.

Cooling Channel Verification

In turbine and aerospace applications, AM enables the fabrication of intricate conformal cooling channels. Neutron imaging can visualize coolant flow and detect blockages or manufacturing deviations in these channels, as the neutrons interact strongly with hydrogen in the liquid or gas medium.

Hydrogen Embrittlement and Trapping Studies

Hydrogen diffusion and trapping are critical issues in high-strength alloys and post-processed AM materials. Neutron imaging can directly observe hydrogen migration or retention within the microstructure, offering insight into long-term reliability and corrosion susceptibility.

Challenges and Developments

Despite its advantages, neutron imaging faces practical adoption barriers. Traditional reactor-based sources are large, expensive, and not easily accessible for routine production inspection. Advances in accelerator-driven neutron sources are changing this.

These smaller, facility-scale systems provide sufficient neutron flux for radiography and CT, making neutron imaging increasingly feasible for industrial quality assurance and research laboratories. Coupled with high-efficiency scintillator screens, digital detectors, and automated reconstruction algorithms, modern neutron imaging systems can deliver high-resolution, high-contrast data in shorter acquisition times than ever before.

Conclusion

As additive manufacturing expands into mission-critical industries, internal consistency and reliability of printed parts become paramount. While x-ray radiography and CT remain indispensable NDT tools, material density and elemental composition limit their effectiveness.

Neutron imaging, through its unique interaction with atomic nuclei, offers complementary and often superior insights, especially in dense metallic components, multi-material assemblies, and hydrogen-sensitive systems. Its ability to penetrate thick alloys, distinguish light elements, and visualize trapped gases or fluids makes it vital for evaluating next generation AM parts.